Double Screen, Double Frame and Double Projection in Expanded Cinema

Friday, May 30, 2014

Atlanta Contemporary Art Center

curated by Andy Ditzler

|

2 x 16mm Double Screen, Double Frame and Double Projection in Expanded Cinema Friday, May 30, 2014 Atlanta Contemporary Art Center curated by Andy Ditzler |

|

|

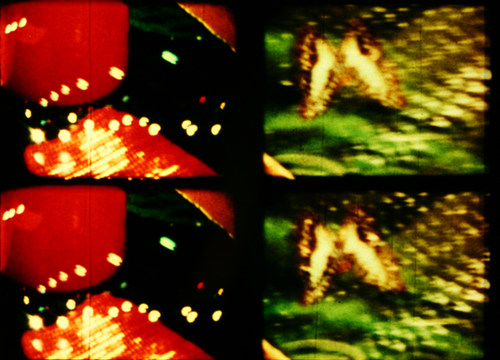

Paul Sharits, Shutter Interface (1975), double 16mm

projection with overlapping color frames |

Program:

Third Eye

Butterfly (Storm de Hirsch, 1968), 9 minutes

A Dance Party

in the Kingdom of Lilliput Nos. 1 and 2 (Takahiko Iimura, 1964/66), 13

min

Shutter Interface (Paul Sharits, 1975), 24 min

all works presented in 16mm dual projection

Like still

photography, a film camera creates the illusion of depth on the flat surface of

a film strip. But for this illusion to be experienced, a film projector

intermittently lights and magnifies successive frames on the film strip

twenty-four times a second and bounces the resulting light patterns off a

screen, creating the further illusion of motion from the strip of still images.

In this sense, any film work is completed by the act of projection. But

tonight's program features three works in which the film strip is not only

displayed but modified by projection, as part of the work. These dual projection

films – each requiring two simultaneously running 16mm projectors – exploit

doubling of the screen to address the many dualities inherent to cinema.

On January 27, 1966, a program of dual-projection works was presented at the

Film-Makers’ Cinematheque in New York, advertised in the Village Voice as

"double screen experiments by double screen experimentalists." The ad hoc nature

of this category notwithstanding, the screening actually presented two key works

of the newly emerging "expanded cinema." Andy Warhol's Outer and Inner Space

premiered that night in two 33-minute reels that were originally shot

sequentially, but projected simultaneously in adjacent frames on the screen.

Barbara Rubin's Christmas on Earth, also shown, featured a unique

exhibition method: instead of projecting side-by-side, one reel is projected

inside the other in superimposition. That event appears to have been Warhol's

very first foray into public double-screen projection; later that fall, he

premiered what is probably the best-known of all double-screen films, The

Chelsea Girls.

Tonight's screening features less-known works from

this era and after, which show how other prominent double-screen

experimentalists used dual projection as a conceptual and aesthetic system of

rich possibilities. In an era when both cinemas and galleries are standardized

for single-screen digital projection, works such as these are more rarely

screened than ever – yet they continue to hold fascination and possibilities

beyond their historical moment.

Despite increasing recognition of women

filmmakers in the context of 1960s underground cinema, the prominent films of

Storm de Hirsch have yet to receive sustained attention. A poet as well as

filmmaker, de Hirsch made films that attempt to expand the boundaries of both

cinema and consciousness, exemplifying the psychedelically inspired side of the

New York underground. Her descriptive note for Third Eye Butterfly

reads in part, "How can dust cover the arrows of light? How can darkness favor

oblivion in the face of light? The variations of soul-touch exist in the auras

of illumination. The Great Eye dominates."

Both title and description

reflect the main motifs seen in the film: light, imagery of drawn or printed

butterflies, flowers, a distinctive "third eye" title logo that appears

throughout the film – and not least, the kineticism of movement itself ("the

arrows of light"). In conjunction with the driving jazz percussion score, the

film is a dazzling experience.

de Hirsch apparently filmed on unslit 16mm

film intended for 8mm projection. In this process, half the film strip is

photographed with a 16mm camera, then is flipped to photograph the other side of

the strip, then is cut lengthwise into 8mm projection film by the lab. When left

unslit and projected as 16mm, the image is doubled both top to bottom and left

to right, producing a grid of four images (and eight images in double

projection). de Hirsch exploits this multiplicity, producing a variety of

kinetic movements across the grid pattern of imagery. de Hirsch constructs

another layer of doubling by superimposing one image over another in many of the

individual shots. Light is depicted as reflected off mirrored surfaces such as

mylar – a doubling of the process of projection, which reflects the light of a

film off the movie screen. Thus, Third Eye Butterfly itself mirrors the

process of film projection and viewing – embodying the self-reflective wisdom

suggested in its title.

Takahiko Iimura's A Dance Party in the

Kingdom of Lilliput is a short film separated into a number of fragmentary

sections depicting activities, some of them performed naked, by the Japanese

artist Sho Kazakura. The sections are arranged seemingly at random, each titled

with the letter "K" (for Kazakura and also Kafka's "Mr. K"), accompanied by

another random letter. (These single-lettered titles reinforce Iimura’s view of

the entire film as a species of concrete poetry.) Dance Party first

existed only as a single-screen film. In the dual projection edition, this

original version comprises the left half of the screen. At some point, Iimura

received a "bad print" of the film, apparently from the lab, and proceeded to

further damage not only the imagery (by hand-scratching the emulsion on the

print), but also the structure (by re-ordering the sections). This second,

damaged version is screened adjacent to the original (which Iimura originally

also intended to newly re-edit for each screening). In this way, the

double-screen version of Dance Party reflects relations between present

(the original version on the left suggests present time as a kind of "official"

experience) and future (the inevitable damage inflicted on projected prints, and

the concurrent re-splicing of experience) – a humorous acknowledgement of the

sometimes nerve-wracking process of film projection, as a metaphor for ongoing

time. Through its playful rearrangement of the alphabet and its disjunct

construction, the left-side original of Dance Party subverts our sense

of an ordered existence; and through the projection of the damaged version on

the right, it incorporates its own physical breakdown into the work, and wittily

transfers our anxieties about disorder to the screen.

Paul Sharits'

Shutter Interface (1975) was constructed as a four-projector gallery

installation work meant to be looped over the run of an exhibition; it is seen

here as a two-projector "economic" adaptation created by Sharits and limited to

twenty-four minutes. Both reels consist entirely of groups of color frames (red,

purple, pink, orange, yellow, blue) lasting from two to eight frames; each group

is separated by a single black frame. On each reel a high-pitched tone

accompanies each black frame. (The film subverts the idea of synchronized sound

and image by having sound only when the screen is blank.) The two reels'

soundtracks are stereo separated so that the left-right divide of the imagery is

reproduced in the room sound. The speed of the film frames is such that at

regular volume, the beeping sounds become a continuous, soothing counterpart to

the imagery, just recognizable as individual tones and in their linear totality.

Sharits gives two options for projecting Shutter Interface. For

the entirety of version A, the two screens overlap precisely, resulting in three

flashing color fields of equivalent size; the middle field necessarily contains

and combines whatever colors are being projected on the left and right reels.

Version B (which we will perform tonight) asks the projectionist to gradually

merge the images together over the course of the screening, following a graphic

diagram showing the two projectors’ positions over the duration of the film. In

this version, the film begins with the two frames completely separate and ends

with the two frames exactly superimposed. As version B of the film progresses,

it transitions from two independent color fields to one color field made up of

two interdependent parts. The individual frames can no longer be seen, only

their combination into a whole. Sharits claimed to have keyed the frame rates of

Shutter Interface to his own biological rhythms. This, together with

the projection technique of gradually merging frames, gives Version B resonant

political and emotional overtones – the relation of the individual to the

collective, the aesthetic to the political, and the personal to the universal.

Through its deliberate lack of development, Shutter Interface is

intended as a contemplative, meditative work; yet it also continuously engages

the viewer with a spectacular, subtle, seemingly endless array of color and

movement. At times the overlapping screens and colors suggest a graphic,

revolutionary "flag" for the kind of cinema Sharits intends, albeit a flag whose

rectangular borders are constantly shifting; at other times, such as when the

screens overlap completely, a gentler pulsation of color suggests distant

lightning. Any number of other interpretations are possible, but the real

subject of this film seems to be its own illusory motion. As Sharits announces

in his title, Shutter Interface is about the intermittent shutter

mechanism of the projector – the rotating blade which causes a given film frame

to blink on and off the screen and thus provide us with the central illusion

that drives motion pictures.

But what is motion in a film that contains

no movement? There is no photographed image of movement across the screen, or

into and out of depth. Rather, the color frames flash on and off, in

combinations nearly too fast to fully comprehend: the motion of consciousness,

via consciousness of motion – or, at least, its illusion. As nearly always in

Film Love shows, the projectors are in the room with the audience. As you watch

Shutter Interface, we encourage you to move among them, to view the

strip of images with its still color frames as it passes through the projector,

to be conscious of cinema's illusion even as we are enthralled by it. Film's

double illusions, motion and depth, are here illuminated by their absence (even

as the projectors multiply). As viewers, we supply the illusion – and in this

sense, Shutter Interface makes projectionists of us all.

Program notes 2014 Andy Ditzler

Thanks to MM Serra and Josh Guilford at

Film-Makers’ Cooperative, and to Atlanta Contemporary Art Center.

|

| Storm De Hirsch, Third Eye Butterfly (1968) |

2 x 16mm

is a Film Love event, programmed and hosted by

Andy Ditzler for Frequent Small Meals. Film Love promotes awareness of the rich

history of experimental and avant-garde film. Through public screenings and

events, Film Love preserves the communal viewing experience, provides space for

the discussion of film as art, and explores alternative forms of moving image

projection and viewing. Film Love was voted Best Film Series in Atlanta by the

critics of Creative Loafing in 2006, and was featured in Atlanta Magazine's Best

of Atlanta 2009.