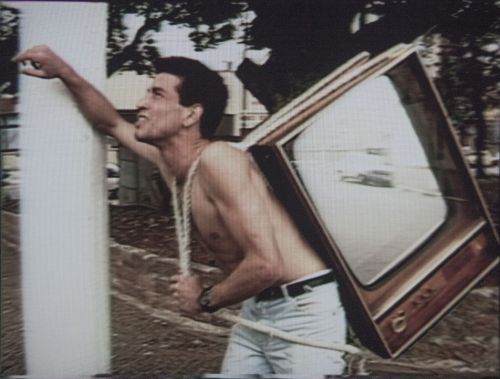

still image from Heróis 2 (Heróis da Decadên(s)ia) (Tadeu Jungle, 1987/2003) courtesy the artist

Politics, Narrative, Collage

April 22, 2016

Atlanta Contemporary Art Center

curated by Andy Ditzler

Notes After Long Silence (Saul Levine, 1989), Super 8mm, 15 minutes

Cartoon Le Mousse (Chick Strand, 1979), 16mm, 15 minutes

Heróis 2 (Heróis da Decadên(s)ia) (Heroes of Decadence) (Tadeu Jungle, 1987/2003), video, 32 minutes, Portuguese with English subtitles

The artists on tonight’s program combine disparate materials into powerful wholes, using the principles of collage in the medium of film or video. Their films break the visual codes of narrative and propaganda, in search of new political possibilities that become visible when we move outside familiar forms.

Since the 1960s, Saul Levine has been making films in 8mm and Super-8mm format. This affordable and user-friendly small gauge medium is associated with home movies and the quotidian, and that is how Levine has often used it – to document his life, friends, and home. This practice has existed alongside his longtime political activism, and several of his major films draw a direct relation between home life and public political work. For Notes After Long Silence, Levine films domestic interiors, women friends talking, children playing, TV footage of B. B. King playing guitar, a construction site with jackhammers, ducks in a pond, and found footage of war and soldiers. He juxtaposes all these images and sounds in a dense, rapid montage. Meanwhile, a daytime TV soap opera comments ironically on the action. Visually, Levine doesn’t let us forget we are watching not just a film, but media. Dark horizontal lines often visibly bisect the frame where Levine made cuts in the film, and the dark space around the television screen means that we often jump between two different size frames.

Notes After Long Silence recontextualizes traditional imagery, but more radically, it deconstructs the way we view and hear imagery and sound, by extending the concept of montage. In traditional montage, different images are directly juxtaposed, causing viewers to form links between them. But instead of polemically using images as symbols, in the manner of Eisenstein, Levine draws a paradoxical subtlety from his barrage of image and sound. By sustaining montage for its entirety, the film becomes visible as a whole rather than through separate individual moments – a kind of collage in time. Formally, the film then expresses a holistic view of Levine’s life. Just as the rapid cutting places the jackhammers, King’s guitar, and sexual intercourse in constant dialogue, to the point where we can perceive them as acting together rather than as being discrete events, the intimacy of domestic and private life becomes inseparable from one’s life in the world. "Personal" and "political" are constructs to be merged, just like the images and sounds from a home movie camera.

In Cartoon le Mousse, Chick Strand presents us with a stark, enigmatic work of found and original footage. In its initial moments, Strand alerts us to the nature of cinema, subtitling the work, "Rituals involving the meditation of pure light trapped in a ridiculous image." A collage of animated films follows, showing a series of animal stars embroiled in threatening situations. We then move indoors for a section of live-action found footage, or "Variations on a bourgeois living room in which the shadow woman hangs herself" – a feminist take on the terrors of domestic space for women, especially in the movies.

This might be the "ridiculous image" trapped in "pure light" – but throughout Cartoon le Mousse, Strand never makes her meanings explicit. As David E. James has written, Strand was "committed to intuition, eroticism, and sensual cognition" in the making of her films. Or as Strand put it, "I do it as I feel it." This approach might account for the film's final section, in which Strand leaves behind found footage for her own original footage, of two women interacting through touch. Visually, neither the women nor their actions are precisely defined – filmed in extreme close-up with a moving camera and darkened lighting, the play between the women becomes very much a cinematic camera play. Here, as James points out, Strand has not only collaged found footage together, but has made Cartoon le Mousse itself a meta-collage of different styles of film. Her insistence on such acts of intuition and eroticism set her films apart from both the analytical feminism of the 1970s and industrial Hollywood. As Saul Levine insists on the inseparability of personal and public life, Strand insists on lyricism and mystery as inseparable from the politics of women’s film.

Tadeu Jungle’s Heroís da Decaden(s)ia was originally completed in Brazil in 1987. An updated version, titled Heroís 2, was released in 2003. Jungle considers Heroís to be a “palimpsest film,” which will be added to and subtracted from over time.

This palimpsest quality is combined with the compilation form that Jungle uses, in which interviews with poets and a priest collide with aggressive performance art actions in the streets of São Paulo, enigmatic lyrical moments, and a dense sound collage featuring music from Brazilian artists and pop stars as well as the Doors, Talking Heads, Prince, and the Beatles. Interestingly, Jungle uses the "remixing" strategy associated with found footage films on his own original footage; he seems to have shot these events specifically to be collaged.

The artistic strategy of recombining disparate elements is redolent of collage, of course, but it also has a specific cultural and historical association in Brazil – namely, anthropophagy, meaning the "cannibalism" of cultural artifacts from elsewhere: to consume and incorporate "the other," in the form of music, writing, art, and film, and to regurgitate this consumption in new, specifically Brazilian, works and forms. As a philosophy and practice, anthropophagy originated in the Brazilian modernism of the 1920s and was rediscovered and championed in the avant-garde of the 1960s. Through its incorporation of United States culture (for example, the direct influence of Jimi Hendrix on the Tropicália artistic and musical movement), the practice of anthropophagy often constituted a direct intervention into debates about the influence of North American culture in Brazil. It thus carried political weight in the fraught social and cultural context of Brazil in the 1960s. Jungle underlines his own connection to the lineage of anthropophagy by concluding Heroís with audio of a notorious onstage political diatribe from 1968 by Tropicália musician Caetano Veloso, one of the most influential advocates of anthropophagy.

Through palimpsest and cannibalism, the elements of Heroís 2 produce a fragmentary quality that Jungle hopes will "oxygenate the traditional forms of narrative." As in the other films on this program, these elements – mysterious on their own – form a cohesive statement when placed in relation to each other. In the tradition of collage works, they allow us to glimpse other realities, temporalities, and political possibilities through the realignment of imagery and the alteration of artistic forms.

Program notes by Andy Ditzler, 2016

Thanks to Robbie Land, Ben Crais, Austyn Wohlers, James Steffen, Atlanta Contemporary, and Canyon Cinema. Special thanks to Tadeu Jungle.

Politics, Narrative, Collage is a Film Love event. The Film Love series provides access to great but rarely seen films, especially important works unavailable on consumer video. Programs are curated and introduced by Andy Ditzler, and feature lively discussion. Through public screenings and events, Film Love preserves the communal viewing experience, provides space for the discussion of film as art, and explores alternative forms of moving image projection and viewing.