Numero 4 (Pip

Chodorov, 1989), super-8, color, sound, 3 minutes (screened on 16mm)

At the Academy (Guy Sherwin, 1974), 16mm, black & white, sound, 5 minutes

Pièce Touchée (Martin Arnold, 1989), 16mm, color, sound, 16 minutes

Cassis (Jonas Mekas, 1966), 16mm, color, sound, 4 minutes

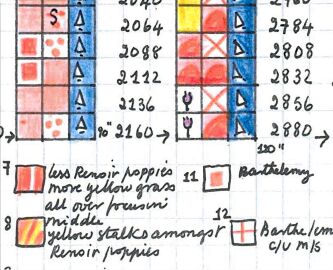

Voiliers et Coquelicots (Sailboats and Poppies) (Rose Lowder, 2001),

16mm, color, silent, 3 minutes

Pasadena Freeway Stills (Gary Beydler, 1974), 16mm, color, silent, 6

minutes

Hand Held Day (Gary Beydler, 1974), 16mm, color, silent, 6 minutes

Stellar (Stan Brakhage, 1993), 16mm, color, silent, 2 minutes

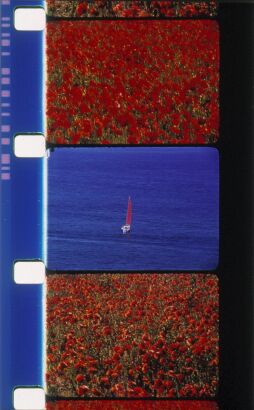

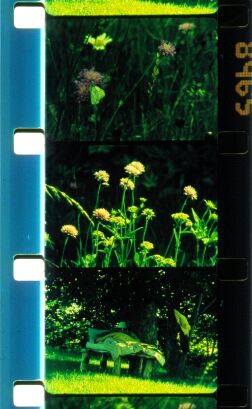

Bouquets 21-30 (Rose Lowder, 2001-2005), 16mm, color, silent, 14 minutes

From the south of France to the cosmos, from Hollywood to Pasadena to Paris,

from silent to sound and color to black & white, from optical printing to hand

painting, and from very fast to very slow – tonight’s films address an unusual

range of filmmaking techniques, concerns, ideas, even geographical origins. Yet

all have one thing in common: they explicitly address the moving image’s origin

in the still frame.

A film consists of a transparent strip of plastic (the “base”), usually made of

a flexible material known as cellulose tri-acetate (popularly called celluloid);

and the “emulsion,” a set of chemicals housed in gelatin, which contains the

image we see. The emulsion is contained on the base in the shape of a “frame,” a

rectangle usually in the proportion of 4 (length) to 3 (width), or 1:33 to 1

(the “aspect ratio”). The frames are arranged sequentially on the base strip. In

the case of 16mm film, there are approximately 40 frames to one foot.

How is it that we see movement when we are really watching nothing more than a

succession of still images? The key is in the way the images are projected, and

in the collusion within our bodies of a physiological and a psychological

phenomenon. When film moves through a projector, it travels through a center

section known as the gate. In the gate, a single frame is held in place long

enough for light from a powerful lamp to project the image through the room and

onto the screen. While this happens, a shutter rotates between the lamp and the

image. This creates an on-off-on-off pattern which means that a single frame is

actually projected onto the screen four to five times. Then, with the shutter in

the closed position, a new frame moves into view. With standard sound films,

this process happens twenty-four times per second, with a “flicker rate”

(shutter speed) of perhaps one hundred twenty per second. Because of this

regular action of the shutter, for almost exactly half the time we watch a film

we are actually completely in the dark.

But we do not notice the darkness which happens 120 times per second on screen,

no do we perceive that we’re watching still images. This is where the physiology

and psychology come in. When we look at a source of light and suddenly close our

eyes, for a brief period we retain on our retinas an image of the light source.

This is called “persistence of vision” and accounts for why we don’t notice the

dark periods during projection. The movement on screen, however, comes from a

psychological process known as the “phi phenomenon.” We see a succession of

images – perhaps a car driving across the screen, or a basketball flying toward

the backboard – and “fill in” the movement between the frames, deducing movement

from what we see. Thus, in the words of film scholar Bruce Kawin, “watching a

movie involves making connections among fragments (frames) and generating a

holistic impression.” (As Kawin also points out, this process is analagous to

the more conscious process of making connections between shots in a movie.)

Each of tonight’s films addresses visually or structurally the mysterious

conjunction between the still frame and the moving image, and thus in one way or

another all the films play with our notions of movement onscreen, and explore

the different speeds at which humans can take in information.

In Pièce Touchée, Martin Arnold takes an eighteen-second excerpt from a

Hollywood b-movie and breaks it down to its individual frames. Rephotographing

the film frame by frame on an optical printer, he seizes on small movements of

the actors, repeating and looping them backward and forward. Seemingly innocuous

motions are transmuted into lascivious gestures. A previously unnoticed shadow

on the wall portends danger. Tensions sexual and otherwise pervade the images.

All of this diabolically reinforces our worst nightmares about the prevalence of

gender stereotypes, and the way they’re encoded in Hollywood films (and by

extension, our culture) at practically a cellular level. To accomplish this

cinematic (and paradoxically humorous) tour de force, made before the advent of

digital editing technology, Arnold worked one frame at a time, building up small

groups of frames, then advancing the group forward or backward by single frames

to create the stuttering motion seen. As he told interviewer Scott MacDonald, “I

photographed 148,000 single images and wrote down the sequences of the frames in

a two-hundred page score. I learned to think movies forwards, backwards, flipped

and upside down.”

Another effect possible with frame-by-frame printing is that of superimposition,

the layering of one or more images. The raw material of Guy Sherwin’s At the

Academy is countdown leader – the kind we see before most films, counting

down from 12 to (usually) 3 – along with other ephemera found on leader –

phrases such as “A BBC TELEVISION FILM,” “PRINTER START” and “JOIN PICTURE

HERE.” Using a contact printer, Sherwin superimposes letters, numbers and

geometric forms both in positive and negative.

On several levels, At the Academy is a witty tribute to the mechanism of film

projection. By extending an ephemeral moment normally used only for the purposes

of focusing the lens, it mischievously prolongs the moment of audience

anticipation before a film begins. The alternation of positive and negative

image produces a dramatic flicker effect which continually reminds us of the

nature of film projection. Finally, the virutoso nature of Sherwin’s

superimpositions constitute not only a dazzling visual spectacle but also a

remarkable graphic work – as delightful to view on the film strip as it is on

the screen.

One of the most common scientific uses of film has been “stop-motion,” in which

frames are taken at a slower rate than the usual twenty-four per second. This

allows us to see actions speeded up far beyond their natural rates, and thus to

study natural and social processes at a glance, so to speak. In both Jonas

Mekas’s Cassis and Gary Beydler’s Hand Held Day, stop-motion is

used to compress an entire day into the space of a few minutes.

Mekas’s film is a study of activity at a port in Cassis, on the southern coast

of France. Sailboats dart across the water like gnats; tourists flit about the

base of a lighthouse. As Cassis shows, human activity can seem quite comic when

speeded up in this manner. In Hand Held Day, however, stop-motion enhances the

natural beauty and drama of a vast landscape. In this film, a set of mountains

in southern California is seen only as a small reflection within a hand-held,

west-facing mirror which acts as an inner frame. The camera sets up three

distinct planes: the close-up of the hand and mirror, the mountains far away in

the mirror, and further away, the eastern sky seen behind the hand. Thus we see

not only multiple planes of movement, but also are able to face in two opposite

directions at once! This perspective allows us to see the eastern sky darken

while the western sky becomes imbued with the dramatic colors of the sunset.

Another film by Beydler is similarly full of paradox and delight. Pasadena

Freeway Stills once again consists of a frame within a frame. We see Beydler

step into the outer frame, and watch him place in the inner frame a still

photograph of highway traffic, taken from a car. He then takes the photo away

and replaces it with a second, almost identical photo, then a third. Gradually,

through editing, this process becomes faster and faster, until the only movement

in the outer frame is the speedy twitch of Beydler’s hands, and the inner frame

becomes “real time.” We discover that the photos in the inner frame are

sequential stills from a movie shot from inside a car traveling down the

freeway. Gradually, the process slows down and the outer frame returns to normal

speed.

As David E. James points out, Pasadena Freeway Stills is “divided and doubled

within itself spatially and chronologically.” In the inner frame, we travel

forward through space in the car, while the larger, outer frame remains

relatively flat. At first, the real-time motion of the hands in the outer frame

causes us to logically identify with the outer frame as “the present,” while the

photos in the inner frame represent the past (as all photos do). Yet this

hegemony falls apart as the inner frame gains in speed and begins to represent

real time. Similarly, the flatness of the still photos is transmuted to depth

via motion, and this depth is contrasted with the flatness of Beydler’s

fingertips pressed against the glass.

Beginning with a single-frame zoom into a photograph on a wall (perhaps a

reference to Michael Snow’s film Wavelength), Pip Chodorov’s Numero 4

gives us a breakneck tour of a seemingly typical day on the streets, sidewalks

and parks of Paris. Going Pasadena Freeway Stills one step further in this

regard, Chodorov presents photos within film, frames within frames, and

representations of spaces within the spaces themselves. Abetted by the pulsing,

interlocking rhythms of the music soundtrack, Numero 4 makes full use of the

energy and dynamism inherent to single-frame filming. Using this time-honored

experimental filmmaking technique, Chodorov, who founded and runs a company

dedicated to making historical experimental film more widely available,

specifically references such masters of the single frame as Jonas Mekas, Marie

Menken, and Rose Lowder.

Lowder lives in Avignon in the south of France and like Chodorov has devoted a

considerable portion of her career to establishing archives, hosting screenings

and generally increasing awareness of experimental film. In her own works she

has forged a unique style of single frame filming which embodies her concerns

with life principles of simplicity and ecology. (Over the past three decades she

and her partner have gradually configured their home in Avignon for a minimum of

energy use and consumerism; for example, they eat organically and vegetarian,

without the use of refrigeration.) Comparing her method of shooting film to that

of the film industry, which sometimes shoots over sixty times the amount of film

that ends up being used, she told Scott MacDonald, “My work is an ecological

statement, in the sense that I do less but try to give it more attention.”

A triumphant example of this working aesthetic are the Bouquets, a series

of one-minute films that number over thirty. Each Bouquet is a tribute to a

particular natural space such as a macrobiotic center or organic farm in the

south of France. And, like a bouquet, each small film reads as a gift to that

space’s human and animal inhabitants. (Detailed descriptions of the spaces

featured in each Bouquet can be read online at

Canyon

Cinema's website.)

In the Canyon Cinema catalog, Lowder describes how she films the bouquets:

“using the filmstrip as a canvas with the freedom to film frames on any part of

the strip in any order, running the film through the camera as many times as

needed.” Thus, she may film a field of flowers using only every third frame

(frames 1, 4, 7 and so on); rewind the film and starting on the second frame,

film a farmhouse every third frame; then rewind to the third frame and film a

differently colored field of flowers. As the film is projected (at silent speed

or eighteen frames per second) the three images merge – not quite superimposed,

but not quite separate. (This technique is the basis for another of Lowder’s

films seen tonight, the delightful Sailboats and Poppies, in which “the

boats sail out of the Vieux port in Marseilles to be amongst the poppy fields.”)

In addition, Lowder will sometimes use a stationary camera on a relatively still

image such as a single flower, and refocus between each frame, creating a unique

type of shimmering onscreen movement – not quite stop-motion – which makes the

flower seem to come alive before our eyes.

Often, the type of movement seen in the Bouquets seems akin to that of rushing

water, appropriate for the films’ concerns with ecology and natural space. And

in Bouquet #28, Lowder makes this connection explicit by alternating images of a

stream in closeup with a group of daisies. Combining these filming techniques,

and using the vast palette of colors available in these locations, Lowder makes

exquisite film bouquets which – true to her ecology – seem to fit all of the

south of France, or maybe the natural world, into a small, personal space, one

frame at a time.

On the opposite scale, Stan Brakhage’s Stellar expands both the frame and

the screen into the cosmos (though its two-minute running time echoes Lowder’s

ecology of the miniature). One of the many hand-painted films which Brakhage

produced late in his career, Stellar invokes stars, the evening sky, and the

spectacular color imagery one associates with astronomical photos. Brakhage

painted each frame by hand, and then printed them at varying rates – as often in

the hand-painted films, many of the images go by at am almost overwhelming

speed, creating an effect somewhere between sensuous and frightening. In

addition to controlling the length of each frame image during the printing

process, Brakhage sometimes holds a single frame onscreen long enough to fade it

out while the more rapid movement of a group of different frames plays out in

superimposition.

Program notes

2007 by Andy Ditzler

THANKS TO Anne Dennington and

Atlanta Celebrates Photography; Rose Lowder; Robbie Land; and Eyedrum.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

David E.

James, The Most Typical Avant-Garde: History and Geography of Minor Cinemas in

Los Angeles. University of California Press, 2005

Bruce Kawin, How Movies Work. University of California Press, 1992

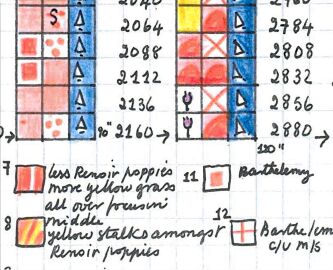

Rose Lowder, unpublished notebook with shooting plan for Sailboats and Poppies

Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 3:

Interviews with Independent Filmmakers. University of California Press, 1998

|

| from Rose Lowder's notes for the frame-by-frame shooting plan for Sailboats and Poppies (courtesy Rose Lowder) |

|

|

| Successive frames from Rose Lowder's Sailboats and Poppies. The top image was shot every third frame; the film was rewound and the sailboat was shot every third frame; then another poppy field was shot every third frame. (courtesy Light Cone and Rose Lowder) | Cinema as ecology: successive frames from Rose Lowder's Bouquet 30, shot in the same way as Sailboats and Poppies (see left). The frames go by at 18 per second. (courtesy Light Cone and Rose Lowder) |

go to STILL/MOVING program 2

STILL/MOVING is a

Film Love event, programmed and hosted by Andy Ditzler for Frequent Small Meals.

Film Love exists to provide access to great but rarely-screened films, and to

promote awareness of the rich history of experimental and avant-garde film. Film

Love was voted Best Film Series in Atlanta by the critics of Creative Loafing in

2006.

Film Love home page

Frequent Small Meals home